The bug fix paradox: why AI agents keep breaking working code

The sledgehammer problem

Here’s a pattern most teams run into: you ask an AI agent to fix a bug. It refactors three helper functions, adds defensive null checks, and writes dozens of new tests for edge cases that were already passing. Even worse, it changes parts of the application that were working just fine. You wanted a scalpel but got a sledgehammer.

Agents are nearly twice as likely as humans to add guard clauses and defensive error handling. Where we'd ask “why is this null?”, the agent adds if (x == null) and moves on. Iteration makes it worse: without proper constraints, the more you talk to an agent, the more it drifts from the original intent. The actual fix, if discovered, is buried under changes that weren’t necessary.

The problem is that you and the agent aren’t working with the same boundary between what to fix and what to leave alone. We built Kiro’s bug-fixing workflow to make that boundary explicit. It’s based on an approach we call property-aware code evolution.

Property-aware code evolution

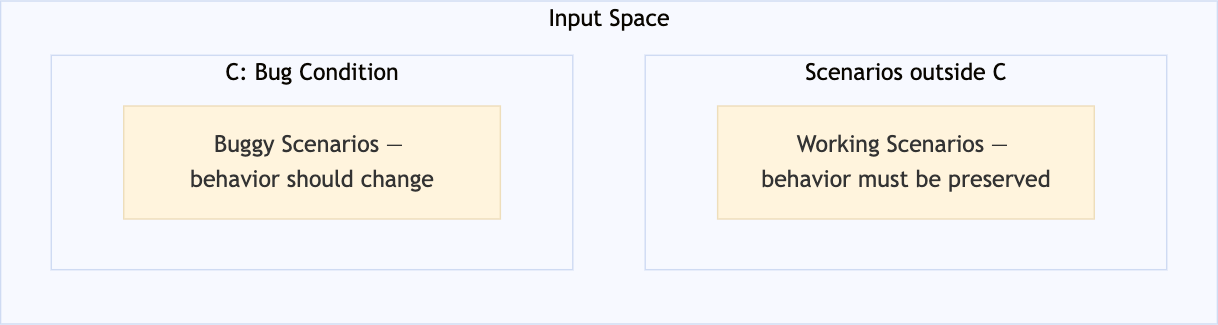

Every bug fix has a dual intent: fix the buggy behavior, preserve everything else. That intent partitions the input space, but the partition usually stays implicit. We can make it explicit and testable.

Bug condition

The bug condition C identifies when the bug triggers. It partitions the input space in two:

Scenarios satisfying C → where the bug manifests. You want change to happen here.

Scenarios not satisfying C → where behavior is correct. You want preservation here.

For example, if deleting a node from a Binary Search Tree (BST) crashes when the right child has no left subtree, C is: node has two children AND node.right.left is None. Every other delete scenario falls outside C and should be untouched.

Every experienced engineer reasons about C, often implicitly. But without C as an explicit, shared artifact, there's no guarantee the agent’s boundary matches yours. When C stays implicit, three things can go wrong:

The agent drifts from the boundary. Even when the bug report is precise, the agent has no persistent record of the boundary. At each step, it re-interprets this boundary from scratch and over multiple steps those interpretations drift away from the original intent.

The agent invents a boundary. When the bug report is vague, the agent fills the gaps with its best guesses, like any engineer would. The difference is the agent doesn’t show them explicitly. By the time you see the mismatch in code review, the patch is already built around it.

The agent can’t check that it respected the boundary. Without an explicit C, there is no systematic way to check if everything else still works. The agent can check its fix, but it can’t check if it stayed within the boundary.

So C draws the boundary. But alone, it isn’t enough. C tells us when the bug triggers, but not what "fixed" means. The postcondition P fills that gap: it defines what the code should do for inputs where C holds, i.e., what should happen for the buggy inputs. For a BST delete that crashes, P is: the delete operation does not crash, removes the node, and preserves the BST invariant.

Without P, the agent can suppress the error with a try/except and call it fixed. P forces it to align with what correct means.

Fix and preservation properties

With property-aware code evolution, we define properties before writing the code. A property is a testable claim: for all inputs satisfying some condition, some guarantee holds. We use the bug condition C and postcondition P to define two properties:

Fix property (C ⟹ P): When C holds, the patched code satisfies P.

Example: The Fix property claims "delete satisfies P on trees where node has two children and node.right.left is None." We can check this by running delete on such trees. If one crashes, the property fails.

Preservation property (not C ⟹ unchanged): When C doesn't hold, the patched code behaves identically to the original.

Example: The Preservation property claims "delete behaves identically on all other trees." Check it by running delete on trees outside C before and after the fix. If the behavior changes, the property fails.

Together, these two properties cover the entire input space and constrain how the agent writes the fix. Any patch must pass the fix property without breaking the preservation property. We call this methodology property-aware code evolution.

Kiro's bug-fixing workflow uses this methodology under the hood. Kiro proposes the bug condition, the postcondition, and the fix and preservation properties. You refine them together, and the resulting spec, tests, and fix that Kiro generates all flow from those properties.

Kiro’s bug fix workflow in practice: a BST delete bug

Here’s a concrete bug report showing a classic data structures bug:

You paste this into Kiro and opt into the bugfix workflow. Kiro doesn’t jump to a patch. It partitions the buggy and non-buggy scenarios, formulates a root cause hypothesis, and tests that hypothesis, before writing a single line of code.

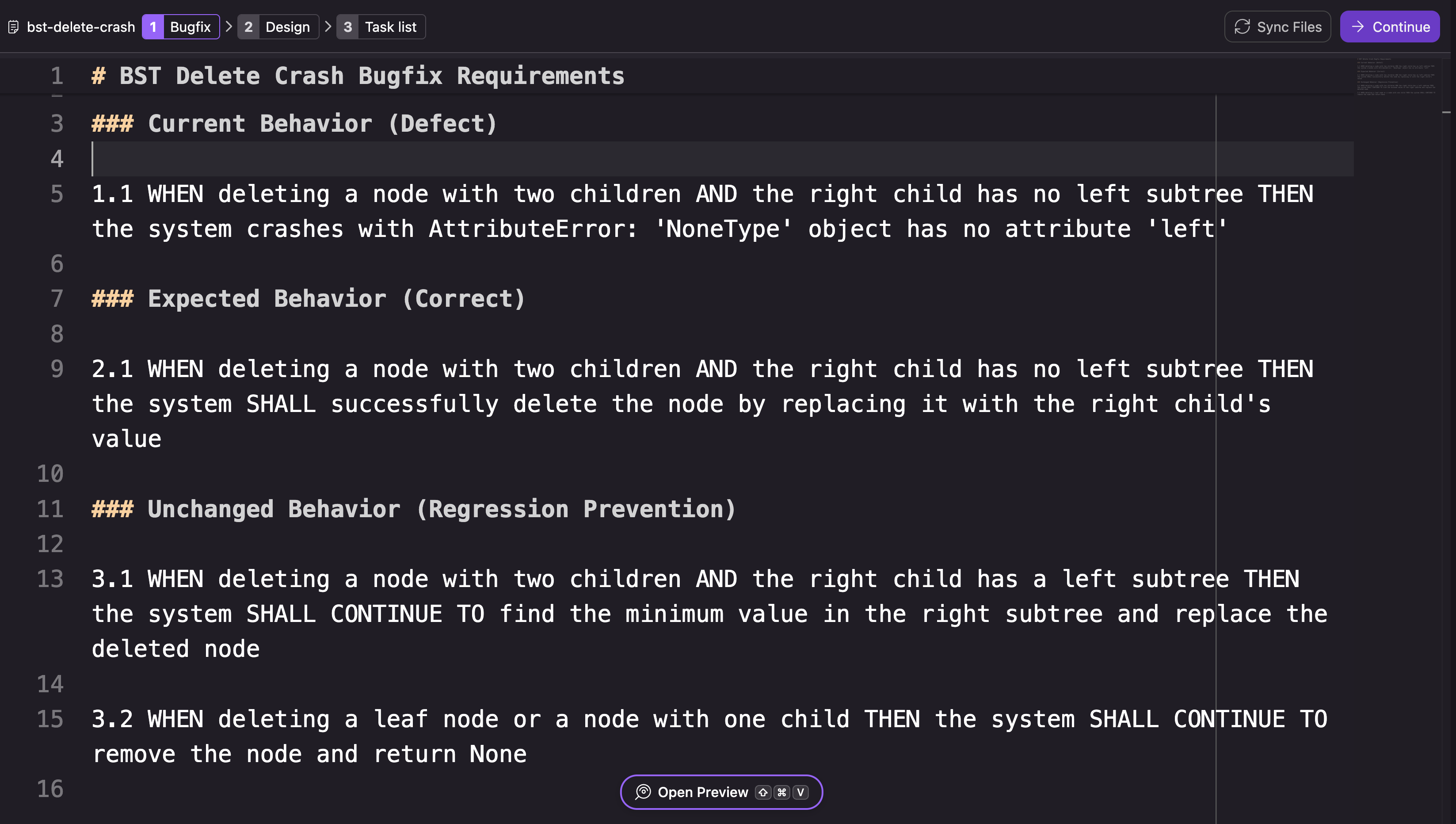

Bugfix doc

Kiro analyzes the bug report and generates a Bugfix document with three requirement categories: the current defective behavior, the expected fix, and unchanged behavior that must be preserved.

This mirrors the partition defined by the bug condition C. Defect and fix requirements target buggy inputs. Preservation requirements identify specific behaviors that must not change.

Design: bug condition and root cause hypothesis

The Bugfix doc partitions the scenarios in natural language. Kiro now formalizes it and investigates why the bug exists.

Formalizing the partition. Kiro extracts the bug condition C from the defect and fix requirements:

Kiro also formalizes what “fixed” means as a postcondition P:

Tracing the root cause. With C and P established, Kiro reads the codebase to build a root cause hypothesis: why do inputs satisfying C crash instead of satisfying P? It traces the execution flow for an input where C holds:

For an input where C holds, say deleting 5 from [5, 3, 7], the trace evaluates:

The hypothesis: _find_min receives node.right.left instead of node.right. When C holds, node.right.left is None by definition, so the call always crashes.

The Checkpoint. Before writing any code or tests, Kiro presents C, P, and the hypothesis for your review. Nothing has been generated yet. If C is too narrow, too broad, or targets the wrong scenario, you get a chance to push back and refine it. If the hypothesis is wrong, the next phase catches it: tests for the fix property should fail on the unfixed code with an AttributeError. If they fail for a different reason, or don’t fail at all, the hypothesis is refuted and Kiro re-analyzes before writing any fix.

The root cause hypothesis makes the design phase more than documentation. It’s a falsifiable prediction. The entire testing strategy that follows is designed to confirm or refute it.

The task plan: testing the hypothesis

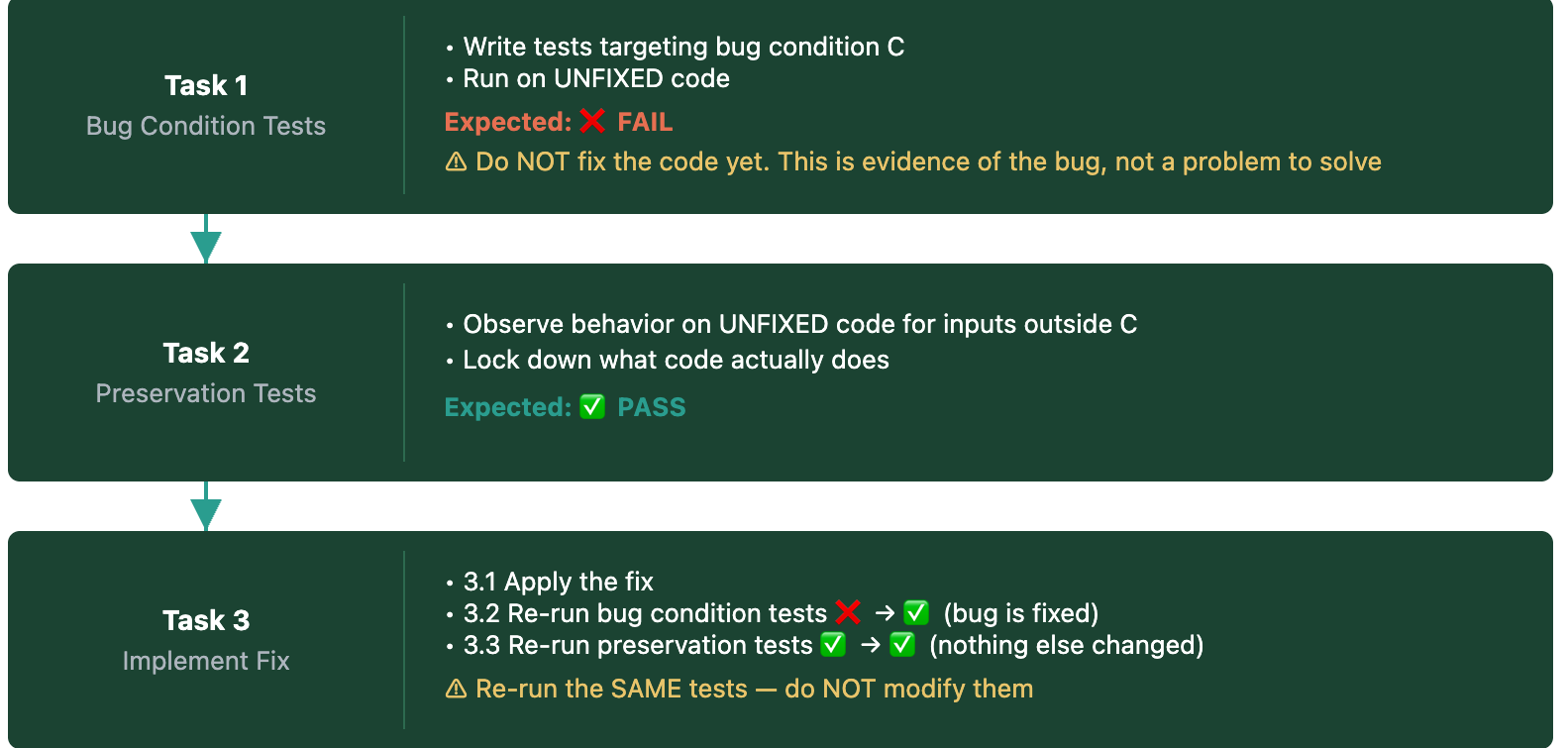

Kiro now has a hypothesis: inputs satisfying C crash because _find_min receives None. The task plan tests it before writing any fix.

Kiro runs every test against the unfixed code first, applies the fix, then retests. It structures the plan into three tasks:

Task 1. Kiro writes bug-condition tests for inputs inside C and encodes the expected behavior (P). Kiro runs them against the unfixed code. They fail. That confirms the bug exists exactly where C predicts.

Task 2. Kiro runs the unfixed code on inputs outside C, records the actual behavior, and writes preservation tests asserting that behavior. Each test should pass against unfixed code.

Task 3. Kiro patches the code according to the root cause hypothesis and reruns the bug-condition and preservation tests. The bug-condition test that failed now passes—the fix works. The preservation tests still pass because nothing else should have changed. If instead, the bug-condition test fails, then the hypothesis was wrong and Kiro flags it and re-investigates before trying another fix. If a preservation test flips, the fix has side effects and Kiro narrows the scope of the patch. Either outcome is actionable.

This is test-driven development’s red-green cycle combined with differential testing. Bug-condition tests are red before the fix, green after. Preservation tests record the unfixed code’s behavior and assert that fixed code behaves the same way on the same inputs; the unfixed code acts as the spec.

Testing before the fix

Both test suites use property-based testing via Hypothesis. Rather than writing tests for specific trees, Kiro declares fix and preservation properties and uses Hypothesis to generate hundreds of random trees to check them (for a deeper treatment of property-based testing in Kiro, see Does your code match your spec?)

Why property-based testing? The bug condition depends on tree structure, specifically whether node.right.left exists. That structure varies combinatorially. Unit tests would require manually constructing dozens of trees to cover it. Property-based tests explore that space automatically, generating hundreds of trees that cover structural combinations a hand-written suite wouldn’t be likely to.

Bug-condition tests check the fix property:

This test encodes the fix property: for all trees where C holds, delete should succeed, remove the node, and preserve the BST invariant. On the unfixed code, this fails with AttributeError because _find_min(None) attempts None.left .

Preservation tests check the preservation property:

This test encodes the preservation property: for all trees where C doesn’t hold — leaf deletes, one-child deletes, two-children deletes where node.right.left exists — behavior is unchanged. On the unfixed code, it passes. That’s the baseline. After the fix, this test must still pass.

The fix

Now that bug-condition tests confirmed the hypothesis and preservation tests captured the baseline, Kiro writes a one-line fix:

Kiro reruns both test suites. The bug-condition tests now pass, validating that the fix works. The preservation tests still pass, validating that nothing else changed.

At scale: a RocketMQ memory leak

Kiro works the same way on larger codebases. Here’s a real-life example: a memory leak in Apache RocketMQ’s HeartbeatSyncer (original PR, SWE-PolyBench). HeartbeatSyncer tracks connected consumers in a concurrent map. Entries are added on register and removed on unregister. But the removal never succeeds. The map grows without bound.

To identify and fix the bug, Kiro follows the same workflow. The root cause hypothesis is a key mismatch:

The insertion key prepends the consumer group, but the removal key does not. They never match. Every unregister is a no-op. The bug condition C is any valid CLIENT_UNREGISTER event where args is non-null and contains a ClientChannelInfo. Every unregister event leaks memory.

The fix is still one line, but validating preservation is harder. There are five distinct code paths through the same listener: null args, non-ClientChannelInfo args, and multi-group registrations among them. The insertion logic and other event types must also remain untouched. Each scenario outside C gets its own preservation test, written and passing before Kiro applies the fix.

Conclusion

With property-aware code evolution, you and Kiro work from the same contract. Kiro drafts the boundary and the hypothesis. You can push back, redraw, tighten the scope, or ask for a different approach. By the time code is written, you’ve both agreed on what changes and what doesn’t.

When the contract breaks down, the workflow makes it evident. If the bug report is too vague to derive C, Kiro flags it before any code is written. When the root cause hypothesis is wrong, the bug-condition test catches it. When the fix has side effects, the preservation tests catch them. Each failure tells you what to do next.

Property-aware code evolution is strongest for changes where the expected behavior can be expressed as functional, testable properties: logic errors, edge cases, runtime exceptions, data handling bugs. For non-functional concerns like performance or race conditions, expressing properties is harder because they are often non-deterministic and require temporal reasoning. Finding the best way to express them as testable claims remains an open question.

Bug fixing is only one application of property-aware code evolution. Feature additions and refactoring have the same dual intent: change behavior within a boundary, preserve everything else. That boundary can be enforced with testable properties. Applying property-aware code evolution beyond bug fixing is an active area of our research.

For now, remember: the next time you file a bug, you’re drawing a boundary. Draw it with Kiro, and the properties keep the fix on the right side.

Further reading

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Aaron Eline, Anjali Joshi, and Margarida Ferreira for their efforts on the property-aware code evolution methodology and Kiro’s bug-fixing workflow.